Once upon a time, Yosemite National Park was a three-season travel destination. Winter presented challenges and potential hardship for visitors. Transportation — a four-day trip from San Francisco by stagecoach, train, or early automobile — was demanding, and destination services were limited or non-existent. Snowflakes signaled danger rather than snow play, and attempting to visit Yosemite in winter was risky at best.

Times have changed. Today, Yosemite is a four-season wonderland, and winter is a magical time to visit. There have been a flurry of memorable moments and characters in the arc of Yosemite’s winter narrative, from pioneering mountain folk to visionary stewards, rebel entrepreneurs to revered skiers, accomplished artists to British royalty. Gather around the crackling fire as we share a few tales of winter history in Yosemite.

Early Days: Heavy Sledding

Yosemite’s first people, the Southern Sierra Miwuk, learned how to weather winter in the region long before the arrival of pioneering Europeans. Even with their well-honed winter survival skills, the Miwuk tended to move from Yosemite Valley and the surrounding high country to Wawona for the winter.

The hard-scrabble settler considered to be the first year-round denizen of Yosemite Valley was James Chenowith Lamon, a Virginian lured to California by the Gold Rush. Lamon built the first log cabin in the Valley near the present-day horse stables. An excellent farmer, he cultivated fruits and vegetables and lived there through the winters of 1862-64, as the rest of Yosemite’s early settlers and visitors decamped to milder foothill elevations as the mercury dipped. Lamon’s apple trees still stand today, near the Curry Village Parking lot, and his memorial monument is one of the largest in the Yosemite Cemetery.

Yosemite remained a very adventurous travel destination until close to the turn of the 19th century. Yosemite National Park was created in 1890 with an Act of Congress, and things began to change. Even so, those hardy first national park visitors endured significant discomfort and hardship – via horseback, stagecoach, and in John Muir’s case, by foot! – to reach Yosemite even in the best of weather.

Transportation vastly improved in 1907 with the advent of the Yosemite Valley Railroad from Merced to El Portal. In December 1907, the railroad added its first winter excursion, but getting to Yosemite remained a multi-mode, tedious journey, even outside of winter.

Breaking the Mirror, Stealing the Sand

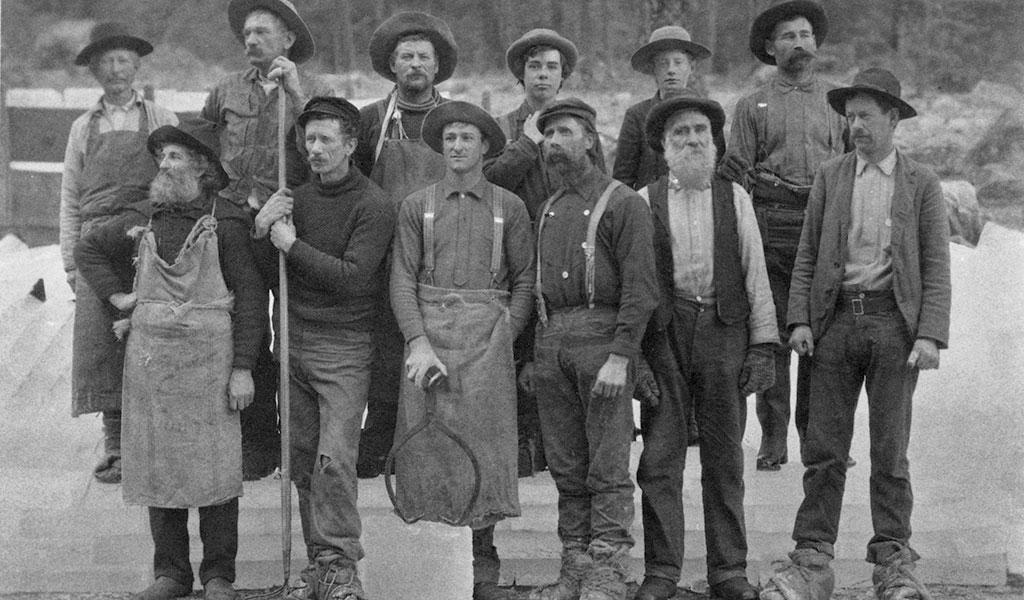

Around the turn of the 20th century, well before electric refrigeration, the fledgling tourism industry in Yosemite Valley faced an operational challenge: food storage for waves of hungry visitors. The solution? Harvesting ice blocks from Mirror Lake. Yosemite’s early hotel industry developed a system of carving ice blocks from the surface of Mirror Lake, moving them to ice houses, and thus making extended food storage safely possible in Yosemite Valley.

Sand was also dredged from Mirror Lake, a practice that started sometime around the 1880s. The sand was spread along icy trails, initially for stagecoaches, horses, and foot traffic. Dredging increased with the growing influx of automobile traffic in the 1930s before eventually being discontinued in the mid 1970s with growing public awareness of conservation and ecology. Today, visitors can see the historical plaque marking this ice and sand activity along the Mirror Lake Trail.

National Park Vision: Stephen Mather

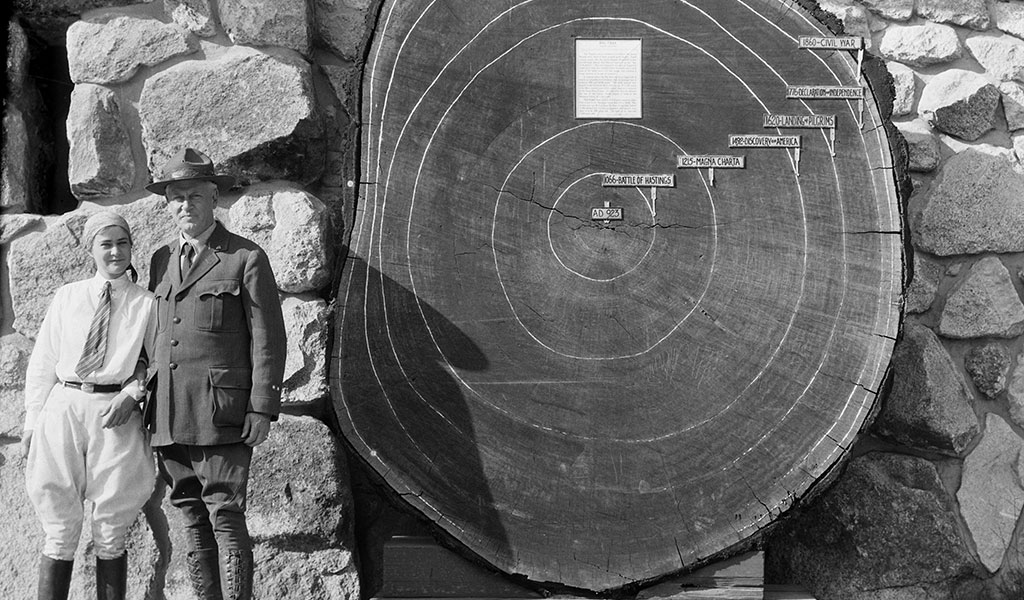

The U.S. National Park Service was formed in 1916, and its first director was Stephen Mather. Mather, a native San Franciscan and UC Berkeley graduate, possessed a passion for conservation – and the clout to back that up. Under his management, government protection dramatically increased for wilderness areas, a big shift from the previous view of wilderness as natural resource storehouses free for commercial exploitation. A visionary steward, Mather leveraged his political connections and significant personal wealth to nurture the national parks ideal.

From NPS headquarters in Washington, D.C, Mather made regular trips to Yosemite between 1916 until retiring in 1929. He believed that “Yosemite is a winter as well as a summer resort,” and during his tenure was instrumental in promoting construction of lodging facilities in the Park as well as securing investment for necessary infrastructure development that made Yosemite a four-season destination.

A central plank of Mather’s platform was the “democratization” of national parks to broaden their access to a much wider cross-section of Americans. To facilitate that, he recognized the need for highway development throughout Yosemite. The successful completion of all-season Highway 140 in 1926 paved the way for Yosemite to finally be considered a winter destination. With a dependably clear and smooth roadway, motorists finally had year-round access to Yosemite Valley. Mather’s “accessible wilderness” legacy lives on in today’s national parks that balance an appropriate amount of development within fragile ecosystems.

Olympic Goals: Don Tresidder

Yosemite’s winter sports culture began to gain momentum with expanding highway access to the snow-covered peaks and valleys. The fundamentals were in place, the next step was a leader who saw the setting through the right lens – ski goggles!

Enter Don Tresidder. A native of Indiana, Tresidder traveled to California in 1914 to attend Stanford University and never looked back. After spending summers working in Yosemite, he married Mary Curry, daughter of Curry Village founders David and Jennie Curry, and in 1925 was named the first president of Yosemite Park & Curry Company, the national park’s new concessionaire.

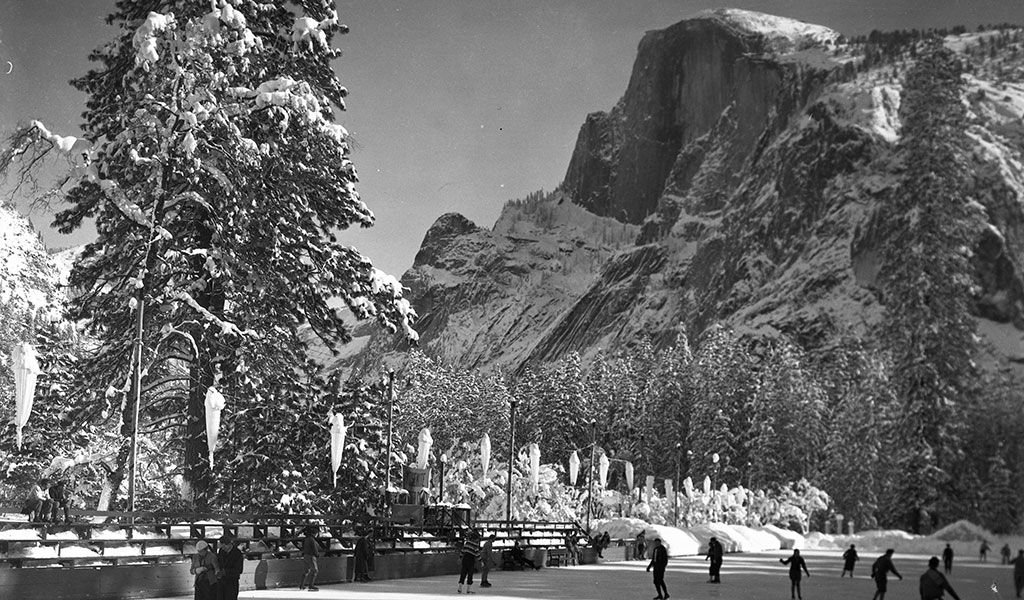

The Park power couple traveled to Switzerland for the 1928 Winter Olympics. Impressed, Tresidder became laser-focused on creating a “Switzerland of the West.” Tresidder campaigned tirelessly to bring the Winter Olympic Games to Yosemite, launching his effort with the construction of an ice rink in Yosemite Valley to host the West Coast Olympic speed skating trials. Since Yosemite was still without a downhill ski venue and other necessary infrastructure, the 1932 Winter Games went to Lake Placid, NY.

Skating in Yosemite Valley was born, however, and in 1933 it hosted the California State Figure Skating Championship. Today visitors can still take a turn on the Curry Village Ice Skating Rink. The exact location of the rink has since changed, but the experience of ice skating in Yosemite Valley continues to be a major winter draw.

Skiing Gains Speed

Tresidder continued to promote Yosemite as a winter sports destination. He founded the Yosemite Winter Club in 1928 to “encourage and develop all forms of winter sports… in the California Sierra to all lovers of outdoor life.” The Yosemite Winter Club was the driving force behind the development of Badger Pass Ski Area, California’s first ski resort. When Wawona Road was completed in 1933, the American West’s first ski lift opened in Yosemite along today’s Glacier Point Road. The “Upski” was a far cry from modern ski lifts; it was basically a six-person sled tugged uphill by heavy metal cables. It earned the moniker “Queen Mary” for its regal, cruise-ship ascent. When Glacier Point Road was extended in 1935, Badger Pass and its historic ski lodge opened. More than 25,000 skiers took to the slopes over the first winter season.

Badger Pass, Yesterday and Today

In addition to the Yosemite Winter Club, Badger Pass owes much of its legacy to Nic Fiore, the legendary ski instructor who arrived in Yosemite from Canada in 1947. For the next six decades, Fiore and his Yosemite Ski School team showed thousands of novices how to snowplow and slalom before he retired in 2004. Fiore became known as “Mr. Badger Pass,” and today the Yosemite Winter Club’s highest honor, the Nic Fiore Award, is presented annually in his name.

Tiny but mighty, Badger Pass is one of only three ski resorts in national parks across the U.S. It offers five chairlifts and is still considered one of the West’s foremost places to learn to ski and snowboard. Fun fact: because it is in a national park, all the snow at Badger Pass is natural and never man-made.

Wintering Royals

Queen Elizabeth II became the first English Monarch to visit Yosemite National Park in March 1983, her first and only trip to California. With Prince Phillip accompanying, the royals stayed at The Ahwahnee and toured Yosemite Valley, marveling at such highlights as Inspiration Point, Tunnel View, Bridalveil Fall, El Capitan, and the Yosemite Chapel, where the Queen attended services. The Queen was also presented with a Native American basket crafted by Yosemite’s celebrated resident weaver Julia Parker, and an original Ansel Adams photograph of Half Dome.

An Epic Winter

When considering monumental events, the stormy 2022-23 winter certainly qualifies as part of the conversation. Yosemite National Park received a historic amount of snow over the winter of 2022-23. The Park’s final snow survey showed Yosemite Valley/Merced River at a record 231% of average and the Tioga Pass/Tuolumne River area also setting a high-water mark of 253% of average – both chart-toppers since snow records were kept.

The Sierra Nevada’s snowy winter created a storybook winter mountainscape. The surging spring runoff recharged Yosemite’s waterfalls to thundering new levels as it provided a much-needed reprieve from recent drought conditions in California. The adage, “When it rains it pours,” was never more apt.

Create Your Own Yosemite Winter History

There’s something about winter that inspires us all. For proof positive, look no further than the images of renowned landscape photographer Ansel Adams. Winter is the backdrop for a number of Adams’ most evocative works, including “Yosemite Valley Winter,” “Clearing Winter Storm” and “El Capitan, Winter Sunrise.”

Yosemite’s favorite shutterbug felt a special affinity for winter – something that any visitor to Yosemite Mariposa County can share today. Winter not only presents some of the best travel values of the year, it also adds an enchanting “snow globe” effect to Yosemite’s soaring mountain scenery. Bring your notebook, sketch pad, and camera, and before you go: check out our seasonal specials page for current offers, Places to Stay for Yosemite Mariposa County accommodations, and Winter Travel section for tips on driving and more.